|

Black and white men, women, and children

cradling wheat, c. 1900.

|

|

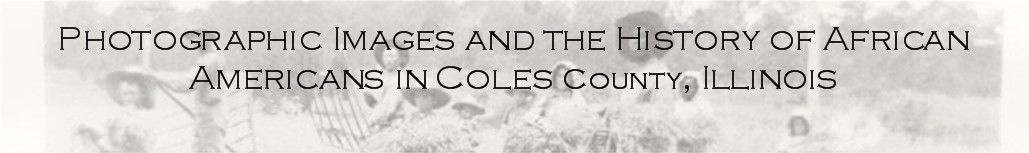

An Historical marker in front of Dr. Hiram

Rutherford's house in Oakland, Illinois.

|

|

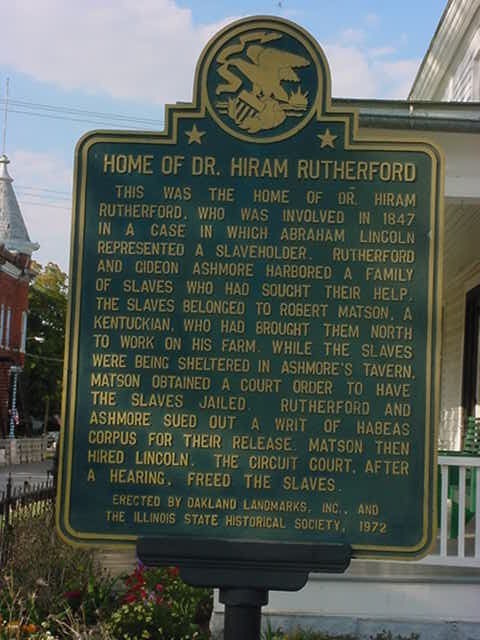

Dr. Hiram Rutherford's House, Pike Street,

Oakland, Illinois. Dr. Rutherford was a popular Physician

and abolitionist in Coles County, Illinois in the 19th century.

|

|

Pemberton Hall, EIU c. 1921 (left to right)

Mrs. Minnie Portee, three white females in the middle unknown,

far right Mr. Arthur Portee. The Portees were cooks in Pemberton

Dining Hall in the 1920's.

|

|

Charles B. Hall, football and track star

at Eastern. He was an ace fighter pilot during WWII with the

famous all negro 99th Fighter Squadron (Tuskegee Airmen),

1944.

|

|

Arthur Anderson Barber Shop in Mattoon, Illinois.

Standing by a customer to the left is Mr. Sidney Williams,

and to his left is Mr. Arthur Anderson (owner), c. 1920.

|

|

Related to lynching was the existence of white

supremacy organizations. As with such organizations which had their

origins in the segregated south, the KKK was formed as a white protective

society which also had the objective of keeping blacks in their

proper place. In Mattoon and Charleston, the Ku Klux Klan (KKK)

was very active in the 1920's. An incident in Mattoon which had

racial undertones involved a black barber named J.P. Cranshaw. In

November 1923, Mr. Cranshaw was arrested in Mattoon with one Mrs.

Mary Evans of Chicago, a white woman for alleged disorderly conduct.

Local newspaper coverage of the incident declared that "Cranshaw's

arrest is stated by Chief Portlock to have been due to the continuous

reports he had been driving out with some white women..." (26)

Mary Evans on her part said "she was at the Big Four passenger

station at eight o'clock Wednesday night standing at the curb, when

a man drove up in an automobile and invited her to take a ride.

She said she did not know the man was colored until they were out

in the country." (27) While it was rumored that she was a local

married woman, the police however, found out that she was a dancer

at the "Black and Tan" Cabaret in Chicago. After her arrest,

an envelope bearing Cranshaw's name and address was found in her

handbag. Cranshaw and the young woman pleaded guilty to the charges.

Cranshaw paid a fine of $204 for himself and another $52 for the

woman. The Ku Klux Klan in reacting to the incident visited Cranshaw's

home on 1509 Shelby Avenue in Mattoon on Thursday night November

15th, where they left a note which read "Jim Cranshaw, your

room is worth more than your company. Leave town at once."

(29) Following this, Cranshaw heeded the warning and left town and

thereby averted being lynched as William Moore.

Even as African Americans were being denied their

rights, they made efforts to establish their citizenship, loyalty

and patriotism to the nation. During the Civil War, African American

men in the area enlisted in the Union Army. In Meyer's words:

Some of the area men did, in fact, go to Boston

to join up. The famous Mass. 54th Regiment was full by the time

they got there. A new black regiment, the Mass. 55th was formed,

and George Manuel is recorded as enlisting in Co H on June 15, 1863.

There are four men listed in Co E as being from Newman: Isaac Rhoades,

Wm. H. Miledam, Francis L. Harrison, and John Curtis. All four made

it to the end of the war and were discharged in 1865. Manuel is

listed as deserting. (30)

In demanding to be enlisted into the Union Army,

African Americans asserted that, "Our feelings urge us to say

to our countrymen that we are ready to stand by and defend our Government

as the equals of its white defenders; to do so with 'our lives,

our fortunes, and our sacred honor,' for the sake of freedom, and

as good citizens; and we ask you to modify your laws, that we may

enlist, --that full scope may be given to the patriotic feelings

burning in the colored man's breast." (31) This patriotic zeal

did not fade with the Civil War. As the photographs in this volume

show African Americans served and fought in subsequent wars involving

the United States.

In spite of the circumscribed nature of African

Americans' freedom in Coles County, they explored both as a group

and as individuals avenues to survive socially and economically.

In the nineteenth century, African Americans relied for the most

part, on agriculture for economic survival in Coles County. Around

Oakland by 1860 black families had fully settled in and farming

the land. As Duane Smith found, by "1860, the James family

was joined by some 27 others, living along a lane known locally

as "negro lane." Five families owned between 400 and 3400

dollars worth of real estate each. These families farmed independently

and worked for neighbors." (32) Others worked as farm laborers

and servants within white households. Furthermore, with time others

branched out into domestic and personal service occupations. For

those who could not secure employment with white employers either

because of limited opportunities or racist attitudes, the only option

opened to them was self-employment. African Americans who went into

self-employment worked as barbers, janitors, blacksmiths, caterers,

hairdressers, washmen and women. Among all these occupations barbering

was the most prominent among blacks in the county. Initially, these

service jobs were not held in high esteem; hence, the predominance

of black barbershops in Charleston and Mattoon.

|